Introduction

Faced with the current and future negative consequences of climate change, the scientific community is calling on governments to take adaptation measures to protect their populations (IPCC, 2022). In this matter, municipal governments have a fundamental role to play (IPCC, 2014) due to the high density of cities and increasing urbanization (Hughes, 2015). Despite the growing involvement of local and regional organizations in the fight against climate change, only a minority of cities have set up adaptation practices, with most focusing instead on greenhouse gas reduction measures (Aguiar et al., 2018; Araos et al., 2016; Bierbaum et al., 2013; Flyen et al., 2018; Hoppe et al., 2014).

In the province of Quebec, as elsewhere, municipalities are beginning to become aware of this issue (Valois, 2017), while nevertheless struggling to follow up with a more prompt development and implementation of adaptation plans and measures. For example, a comparison of the province’s two largest cities shows that Montreal has put forward a formal adaptation policy, while Quebec City has opted instead for ad hoc measures. The remainder of this article defines and distinguishes between these two approaches and explains the reasons behind these strategic differences.

The governance of climate change adaptation on an urban scale

The last decade has seen a proliferation of studies on climate change adaptation. Their publication in general and scientific literature provides an initial outline of the challenges and opportunities structuring local government decisions. Despite the growing interest of cities and the research community in climate change governance, an understanding of the brakes and levers facing local governments remains limited (Bierbaum et al., 2013; Bulkeley et al., 2009; Picketts, 2015; Vogel and Henstra, 2015; Wang, 2013). While the literature identifies several factors promoting or limiting adaptation measures at the municipal level (as outlined in the following paragraphs), it rarely distinguishes between the different strategies adopted by cities and does not examine their evolution over time. To supplement this contemporary perspective, I also return to the relevance of analyzing municipal strategy using an incremental approach, as described in Lindblom (1959).

At present, two main themes stand out in the scientific literature on climate change adaptation at the local level. On the one hand, the literature emphasizes the role of human, financial and informational resources in understanding the efforts put in place by cities (Aguiar et al., 2018; Bierbaum et al., 2013; Burch, 2010a, 2010b; Robinson and Gore, 2005; Schwartz, 2016). For example, in a survey of 147 European cities, Aguiar et al. (2018) note that lack of personnel and financial resources are the main barriers limiting adaptation efforts. In the same vein, the lack of precise data on the future impacts of climate change complicates decision-making, as it is unknown to what extent these will affect individual cities (Bierbaum et al., 2013; Dulal, 2017). Although the consequences of climate change on a municipal scale are still poorly understood, we already know that the most vulnerable populations will bear the brunt of its negative effects (Blangy et al., 2018).

To address these difficulties and the lack of resources, several studies report that collaboration has proven particularly effective (Bidwell et al., 2013; Cloutier et al., 2014; Hayes et al., 2018; Hughes, 2015; Kalesnikaite, 2018; Woodruff, 2018). In the Canadian context, McMillan et al. (2019) suggest that financial and scientific support from the federal government is crucial to encourage local initiatives related to climate change adaptation. In the absence of such support at the federal or provincial level, cities have the option of collaborating with other municipal governments (Flyen et al., 2018), consulting specialists in the field (Hayes et al., 2018) or taking part in political networks (Campos et al., 2017; Flyen et al., 2018) such as C40[1].. By collaborating in this way, municipalities have the opportunity to benefit from the experience and knowledge of their partners and sometimes even from funding to make up for the lack of resources they face. Collaborative approaches can foster the inclusion of different types of knowledge, including Indigenous knowledge, the consideration of social and local concerns as well as the legitimacy of decisions, thereby strengthening local capacities (Anguelovski et al., 2016; Ford et al., 2016; Seasons, 2021).

On the other hand, research shows the importance of culture and leadership in local government. The culture of collaboration within a local government is particularly important, according to existing research. Bierbaum et al. (2013) argue that redundant, even contradictory, adaptation practices are sometimes in place within a local government structure, limiting its effectiveness in tackling climate change. Similarly, Berry et al. (2015) suggest that it is common in cities for adaptation policies and those aimed at reducing greenhouse gases to be in conflict, negating desired outcomes.

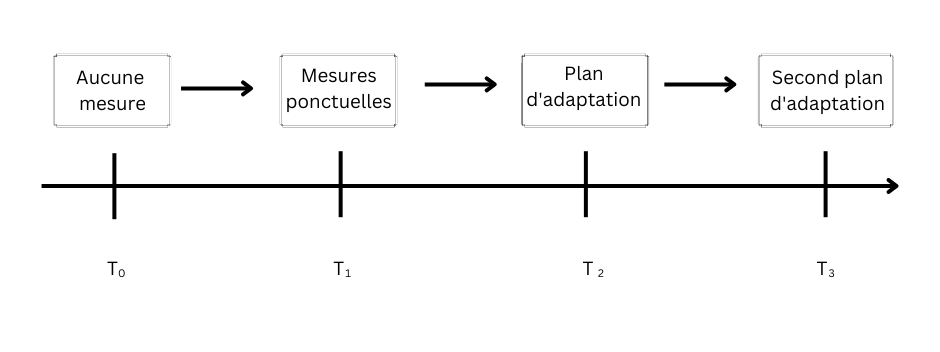

Faced with these obstacles, it is pertinent to question not only the factors influencing decision-making at the municipal level but also the evolution of the strategies adopted by cities. In this context, Lindblom’s (1959) incremental approach is particularly useful since it enables us to understand the decision-making process and the progression of the measures taken. The central idea of this decision-making model is to make small changes to policies over time, so that decisions can be reversed if they prove less than optimal. According to this approach, policies are relatively stable, and changes are made on an ad hoc basis to respond to difficulties as they arise. The incremental model applies particularly well to so-called complex problems such as climate change (Bendor, 2015) and helps to understand the trajectory of Quebec City and Montreal, as demonstrated below.

Cases and method

The comparison made between the cities of Montreal and Quebec City follows Mills’ logic that similar cities (i.e., with comparable characteristics) have chosen divergent policies (i.e., their adaptation strategy, in this case)[2]. Indeed, both cities have large populations compared with other Quebec cities (over 500,000 people), generate similar levels of revenue and are organized according to a similar local and regional administration (i.e., being structured as a metropolitan community). Nevertheless, despite these similarities, their relationship to adaptation is distinct. While the City of Montréal has chosen to put in place a formal climate change adaptation policy, the City of Quebec has initiated a process, but has not yet adopted a plan as such.

To explain this difference, three distinct methodologies were used. Firstly, a media analysis of the province’s main French-language newspapers (La Presse, Le Devoir, Le Journal de Montréal, Le Journal de Québec and Le Soleil) was carried out between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2019 to measure the importance of environmental issues in the media[3]. A total of 370 newspaper articles dealing with various environmental issues at the municipal level were read and coded using NVivo software. Secondly, a literature review of key municipal and provincial policies related to climate change adaptation was conducted to identify support measures offered to municipalities by the Quebec government and to establish a sequence of environmental policies for each city. Thirdly, five semi-structured interviews were conducted with municipal officials between April and October 2020. These interviews were conducted by video-conference, due to health restrictions in place at the time. They served to corroborate and complement the results obtained by the other data collection methods.

Results

As mentioned above, the cities of Montreal and Quebec have adopted divergent strategies to adapt to the negative impacts of climate change. In the case of Montreal, an adaptation plan has been put in place for the Montreal agglomeration (i.e., all cities on the island of Montreal). In the case of Quebec City, despite several attempts, the city has not succeeded in adopting an adaptation plan and has instead implemented ad hoc adaptation measures. In both cases, we also note that the cities face significant challenges in implementing their strategies.

Strong leadership at the City of Montréal

Developed under the leadership of the City of Montréal, a climate change adaptation plan was adopted for the territory of the agglomeration of Montreal in 2015 (Ville de Montréal, 2015). Concretely, the plan was created in collaboration with the boroughs of Montreal as well as the independent cities on the territory of the island of Montreal. The approach was voluntary insofar as the various administrative units could themselves decide on the actions they wished to implement according to their resources and budgetary context (Bünzli, 2018; Confidential interview, 2020). As a result, the plan mainly brought together ad hoc measures already underway within the boroughs and linked towns (Confidential interview, 2020). Despite this rather favourable context, the implementation of the measures of the adaptation plan exposed a number of difficulties, including financial constraints, lack of coordination between the various administrative units and lack of accountability (Bünzli, 2018; Confidential interviews, 2020). Nevertheless, the entire decision-making process surrounding the adaptation plan benefited from clear political support from the municipalities’ elected officials (including the mayor), regardless of their partisan affiliation,[4] as evidenced by public speeches by Mayor Valérie Plante and her predecessor, Denis Coderre:

“Despite our mitigation efforts, some of the climatic upheavals we feared are already being observed: heat waves, heavy rain, ice storms, and so on. A strategy to limit their negative consequences is essential for our administration and for our citizens.” Denis Coderre (Ville de Montréal, 2017b; own translation).

“For a number of years now, the City of Montréal has played a leading role in implementing concrete measures to address climate change. […] [W]e reiterate our commitment to making Montreal a proactive and committed city not only in reducing greenhouse gases but also in responding to the impacts they generate.” Valérie Plante (Ville de Montréal, 2018b; own translation).

This political support continued during the drafting of a second adaptation plan (the Montréal Climate Plan) adopted in 2020 (Ville de Montréal, 2020), which included new measures (Confidential interview 2020)[5]. In our view, this illustrates Montreal’s incremental trajectory over a period of several years.

The difficulty of adopting an adaptation plan in Quebec City

As in the case of Montreal, Quebec City has stated its desire to adopt a formal climate change adaptation policy, and has taken steps in this direction. The city has been working on an adaptation plan (Ville de Québec, 2016), which has never been adopted, despite several attempts by the city council (Confidential interview, 2020). This failure can be explained, firstly, by the lack of clear leadership on environmental issues on the part of council members and the mayor in particular and, secondly, by the difficulty of effectively communicating the importance of climate change adaptation to council members. Another explanation, put forward by Scanu (2019), suggests a lack of interest in environmental and climate issues on the part of both the city council and the general population of Quebec City. Although the adaptation plan was never adopted, ad hoc adaptation measures were nonetheless put in place by civil servants in the various departments. Professional staff and managers recognize, however, that the adoption of an adaptation plan would have facilitated the implementation of these measures, which would then have benefited from a clear directive from elected officials. The case of Quebec City illustrates that ad hoc measures can be taken in the absence of an adaptation plan. This observation is in line with Lindblom’s model (1959), according to which small actions are easier to adopt than larger ones.

Comparative analysis

These results illustrate that the adoption and implementation of climate change adaptation measures follows an incremental process in which policy changes are made little by little over a long period (see Figure 1). In particular, the results underline the difficulty cities have in innovating quickly, and suggest the emergence of a two-stage mobilization pathway. Firstly, ad hoc measures are implemented by various municipal departments in response to specific problems (e.g., revising snow-clearing techniques to take account of rainy days in winter). Secondly, these measures are grouped together in an adaptation plan adopted by the municipal council or, in the case of Quebec City, implemented on an ad hoc basis, despite the absence of an adopted plan. That said, it is just as difficult to implement ad hoc measures as it is to implement actions included in the adaptation plan. These results show the importance of looking at the evolution of policies over time in order to understand how cities are progressing in adapting to climate change, alongside the difficulties they face throughout the political process.

Figure 1: Incremental trajectory of climate change adaptation in Quebec municipalities[6]

Conclusion

The results presented here show that some municipalities have implemented climate change adaptation measures in the absence of an adaptation plan, and at times, as in the case of Quebec City, favoured ad hoc measures. In this context, it is imperative to learn more about the scope of these measures and the challenges that municipal administrations must overcome to make these adaptation efforts a reality. Although our understanding of the issues surrounding climate change adaptation at the municipal level is improving thanks to the work of a number of researchers (Baril, 2022; Bünzli, 2019; Scanu, 2019; Valois, 2017), the incremental aspect of climate governance remains little studied. This notion is all the more important as results from an incremental approach can take time to materialize. If delay occurs, populations—particularly the most vulnerable—could suffer more from the negative consequences of climate change, which are set to increase in magnitude over the next few years. In this context, it is imperative that the scientific community pay greater attention to climate-related governance issues, including the inclusion of participatory democracy in the development of climate change policies, the impact of these policies on vulnerable populations, and the selection of collaborative governance mechanisms to foster climate change adaptation policies and protect the most vulnerable individuals.

[1] The C40 is a network of some 100 of the world’s largest cities (including Montreal), dealing with climate and environmental issues within local government.

[2] This methodology is known as “Most Similar Research Design.”

[3] Although these newspapers cover provincial and federal news, the media analysis focused on municipal news only.

[4] The media analysis shows that no elected official publicly opposed the adoption of an adaptation plan.

[5] The City of Montréal’s Climate Plan includes measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to adapt to climate change.

[6] This concept of the municipal trajectory in the field of climate change adaptation was developed following an analysis of the adaptation strategies of six municipalities of the province of Quebec: Montreal, Quebec City, Laval, Longueuil, Sherbrooke and Saguenay (Bourgeois, forthcoming).

To cite this article

Bourgeois, E. (2022). The incremental trajectory of climate change adaptation in Quebec municipalities. In Cities, Climate and Inequalities Collection. VRM – Villes Régions Monde. https://www.vrm.ca/the-incremental-trajectory-of-climate-change-adaptation-in-quebec-municipalities

Reference Text

Bourgeois, Eve. 2022. « Climate Change Adaptation in Quebec Municipalities: Explaining the Measures Chosen by Local Governments ». Thèse doctorale, University of Toronto.

References

Anguelovski, I., et al. (2016). « Equity Impacts of Urban Land Use Planning for Climate Adaptation: Critical Perspectives from the Global North and South ». Journal of Planning Education and Research, 36(3), p. 333-348.

Aguiar, Francisca C., et al. (2018). « Adaptation to Climate Change at Local Level in Europe: An Overview ». Environmental Science & Policy, 86, p. 38-63.

Araos, Malcolm, et al. (2016). « Climate Change Adaptation Planning in Large Cities: A Systematic Global Assessment ». Environmental Science & Policy, 66, p. 375-382.

Baril, Pierre-Luc. (2021). Les instruments municipaux de la transition écologique : une étude comparative en milieu rural québécois. Mémoire de maîtrise, Université du Québec à Montréal.

Bendor, Jonathan. (2015). « Incrementalism: Dead yet Flourishing ». Public Administration Review, 75(2), p. 194-205.

Berry, Pam, et al. (2015). « Cross-Sectoral Interactions of Adaptation and Mitigation Measure ». Cross-Sectoral Interactions of Adaptation and Mitigation Measure, 128, p. 381-393.

Bidwell, David, Thomas Dietz et Donald Scavia. (2013). « Fostering Knowledge Networks for Climate Adaptation ». Nature Climate Change, 3, p. 610-611.

Bierbaum, Rosina, et al. (2013). « A Comprehensive Review of Climate Adaptation in the United States: More than before, but Less than Needed ». Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 18(3), p. 361-406.

Blangy, Sylvie et al. (2018). « OHMi-Nunavik : A Multi-Thematic and Cross-Cultural Research Program Studying the Cumulative Effects of Climate and Socio-Economic Changes on Inuit Communities », Écoscience, 25(4), p. 311-324.

Bourgeois, Eve. (À venir). Climate Change Adaptation in Quebec Municipalities: Explaining the Strategy Chosen by Local Governments. Thèse de doctorat, Université de Toronto.

Bulkeley, Harriet, et al. (2009). Cities and Climate Change: The Role of Institutions, Governance and Urban Planning. Report prepared for the World Bank Urban Symposium on Climate Change.

Bünzli, Noé. (2018). Adaptation en contexte municipal québécois : débroussaille et exploration de la MRC de Memphrémagog. Rapport de recherche : stratégies durables d’adaptation aux changements climatiques à l’échelle d’une MRC.

Bünzli, Noé. (2019). Entre complexité et mise en œuvre : l’interprétation de l’adaptation aux changements climatiques en contexte municipal québécois. Mémoire de maîtrise, Université de Montréal.

Burch, Sara. (2010a). « In Pursuit of Resilient, Low Carbon Communities: An Examination of Barriers to Action in three Canadian Cities ». Energy Policy, 38, p. 7575-7585.

Burch, Sara. (2010b). « Sustainable Development Paths: Investigating the Roots of Local Policy Responses to Climate Change ». Sustainable Development, 19, p. 176-188.

Campos, Inês, et al. (2017). « Understanding Climate Change Policy and Action in Portuguese Municipalities: A Survey ». Land Use Policy, 62, p. 68-78.

Cloutier, Geneviève, et al. (2014). « Planning Adaptation Based on Local Actors’ Knowledge and Participation: A Climate Governance Experiment ». Climate Policy, 15(4), p. 458-474.

Dulal, Hari Bansha. (2017). « Making Cities Resilient to Climate Change: Identifying “Win-Win” Interventions ». Local Environment, 22(1), p. 106-125.

Entrevues confidentielles. (2020, du 8 avril au 3 juillet). Entretiens téléphoniques.

Flyen, Cecilie, et al. (2018). « Municipal Collaborative Planning Boosting Climate Resilience in the Built Environment ». International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment, 9(1), p. 58-69.

Ford, J. D., et al. (2016). « Community-Based Adaptation Research in the Canadian Arctic ». Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change, 7, p. 175-191.

Hayes, Adam L., et al. (2018). « The Role of Scientific Expertise in Local Adaptation to Projected Sea Level Rise ». Environmental Science and Policy, 87, p. 55-63.

Hoppe, Thomas, Maya M van den Berg et Frans HJM Coenen. (2014). « Reflections on the Uptake of Climate Change Policies by Local Governments: Facing the Challenges of Mitigation and Adaptation ». Energy, Sustainability and Society, 4(1).

Hughes, Sara. (2015). « A Meta-Analysis of Urban Climate Change Adaptation Planning in the U.S. ». Urban Climate, 14, p. 17-29.

Kalesnikaite, Vaiva. (2018). « Keeping Cities Afloat: Climate Change Adaptation and Collaborative Governance at the Local Level ». Public Performance & Management Review, p. 1-25.

IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp.

IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3056 pp

Lindblom, Charles. (1959). « The Science of “Muddling Through” ». Public Administration Review, 19, p. 79-88.

McMillan, Troy, et al. (2019). Local Adaptation in Canada. Federation of Canadian Municipalities. Fédération canadienne des municipalités, Université de la Colombie-Britannique et Université de Waterloo.

Picketts, Ian M. (2015). « Practitioners, Priorities, Plans, and Policies: Assessing Climate Change Adaptation Actions in a Canadian Community ». Sustainability Science, 10(3), p. 503-513.

Robinson, Pamela J., et Christopher D. Gore. (2005). « Barriers to Canadian Municipal Response to Climate Change ». Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 14(1), p. 102-120.

Scanu, Emiliano. (2019). « Climate Change, Urban Responses and Sociospatial Transformations: The Example of Quebec City ». Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 28(2), p. 1-15.

Schwartz, Elizabeth. (2016). « Developing Green Cities: Explaining Variation in Canadian Green Building Policies ». Canadian Journal of Political Science, 49(4), p. 621-641.

Seasons, Mark. (2021). « The Equity Dimension of Climate Change: Perspectives From the Global North and South ». Urban Planning, 6(4), p. 283-286.

Valois, Pierre, et al. (2017). Niveau et déterminants de l’adaptation aux changements climatiques dans les municipalités du Québec (OQACC-006). Observatoire québécois de l’adaptation aux changements climatiques.

Ville de Montréal. (2015). Plan d’adaptation aux changements climatiques de l’agglomération de Montréal 2015-2020 — Les mesures d’adaptation. En ligne. (page consultée le 24 septembre 2020).

Ville de Montréal. (2017). Partenariat entre la Ville de Montréal et Ouranos pour l’adaptation aux changements climatiques. En ligne. (page consultée le 1er octobre 2020).

Ville de Montréal. (2018). Entente de collaboration entre la Ville de Montréal, le C40, la Fondation David Suzuki et la Fondation Familiale Trottier. En ligne. (Page consultée le 1er octobre 2020).

Ville de Montréal. (2020). Plan climat 2020-2030. En ligne. (Page consultée le 15 décembre 2020).

Vogel, Brennan, Daniel Henstra et Gordon McBean. (2018). « Sub-National Government Efforts to Activate and Motivate Local Climate Change Adaptation: Nova Scotia, Canada ». Environment, Development and Sustainability, 22, p. 1633-1653.

Woodruff, Sierra C. (2018). « City Membership in Climate Change Adaptation Networks ». Environmental Science and Policy, 84, p. 60-68.