Lucie Morin, PhD candidate in social work (Université de Montréal), Sonia Racine, knowledge mobilization consultant (Communagir), Denis Bourque, professor, Department of Social Work (UQO), André-Anne Parent, professor, School of Social Work (Université de Montréal), René Lachapelle, research professional, Centre de recherche et de consultation en organisation communautaire (UQO), Christian Jetté, professor, School of Social Work (Université de Montréal), Stéphane Grenier, professor, School of Social Work (UQAT), Dominic Foisy, professor, School of Social Work (UQAT), Sébastien Savard, professor, School of Social Work (University of Ottawa), Serigne Touba Mbacké Gueye, professor at the School of Social Work (UQAT), Geneviève Le Dorze-Cloutier, PhD candidate in social work (Université de Montréal), Ariane Hamel, master’s student in social work (UQO ) and Charlotte Goglio, master’s student in social work (UQAM).

Introduction

Coastal erosion on the Gaspé Peninsula and the Magdalen Islands, heat islands in Montreal and Quebec City, forest fires in Abitibi-Témiscamingue, and flooding in Baie-Saint-Paul are just a few examples of how climate change is affecting Quebecers in different ways. The World Health Organization (2021) has recognized climate change as the greatest health threat of the 21st century, a threat that targets social determinants of health like food, housing, income, mobility, and access to green and blue spaces.

In recent years, Quebec has seen a multitude of stakeholders join forces to improve people’s living conditions. A substantial body of expertise has been developed in the field of community action, with a focus on social development (Bilodeau and al., 2014). Research by René Lachapelle and Denis Bourque (2020) on integrated regional development has highlighted the difficulties faced by various groups in seeking to develop action plans that account for all dimensions of development (social, economic, cultural, and environmental). The climate and environmental crisis has been creating new conditions that could finally prompt a more integrated approach to regional development by requiring local authorities to ramp up their efforts to address environmental issues through their priorities and activities. While community groups and organizations offer assistance to those struggling to make ends meet, grassroots environmental movements are waging a battle to save humanity and avoid the end of the world. Notwithstanding differences in scale and context, there is a clear opportunity to unite these twin efforts.

State of the Academic Literature

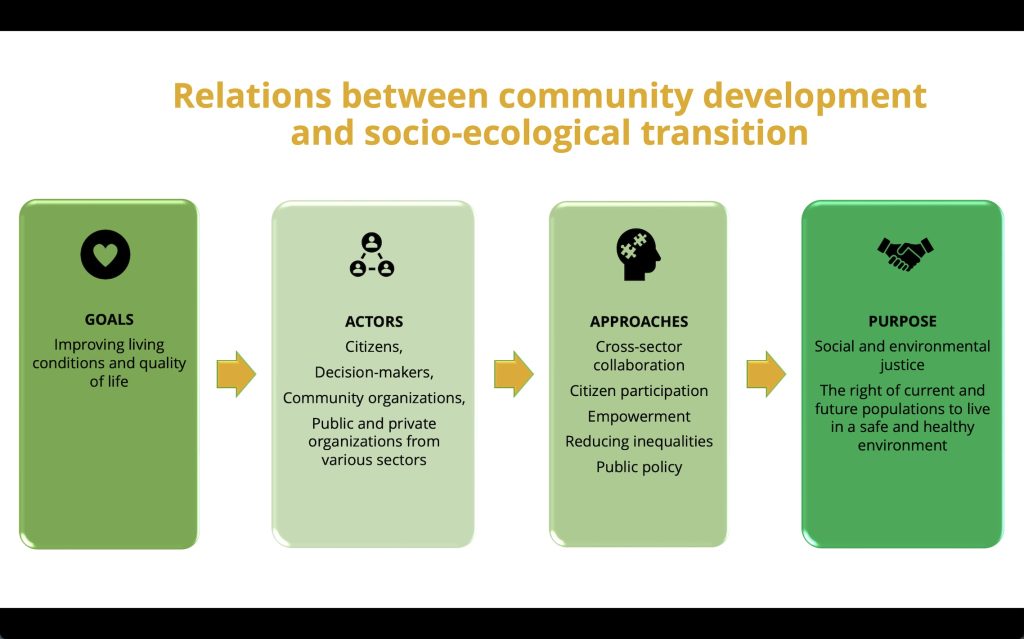

There are currently more than 250 regional development processes (RDPs) focused on social development underway in Quebec (Morin and al., 2023). We define RDPs as different forms of structured collective action within a given region that address shared issues related to living conditions and quality of life by calling on the populations and stakeholders concerned (institutional, community, private) to identify priorities, mobilize resources, and implement appropriate responses (Mbacké Gueye and al., 2023). In concrete terms, RDPs take action to improve the material or social circumstances under which people are born, grow up, live, work, and grow old; in many cases, they serve to drive social change (Lachapelle & Bourque, 2020; Parent & Bourque, 2016). Rooted in a regional context, RDPs have the capacity to mobilize people and resources. Their focus on community development makes them ideal for tackling social and environmental issues. And they often involve community workers—such as community organizers active in the fields of health and social services, or individuals hired to coordinate RDPs—reaching out to groups, organizations, and communities (Mercier & Bourque, 2021). Comeau (2010) has argued that community workers can make a significant contribution to collective environmental action, given their expertise in identifying and managing factors that threaten to undermine solidarity. In times of social disruption or upheaval, the resilience of local communities and their capacity to deal with crises often depends on solidarity, social cohesion, and efforts undertaken on a regional scale (Huq, 2022). From a theoretical perspective, the community development approach can produce social changes aligned with the socioecological transition (see Figure 1), based on the common threads of intersectorality, democracy, justice, and regional focus.

Source: Courtemanche and al., 2022.

A socioecological transition (SET) is necessary to ensure people’s health and well-being while reducing social and ecological inequalities (Senay and al., 2023). Inspired by the work of Audet amd al. (2015), organizations involved in the transition movement and that participated in the “community projects” initiative launched by Partenariat Climat Montréal in 2021 have defined the concept as follows:

[…] a transition from the current state of the system to a more socially just, inclusive, and environmentally sustainable state. This will be made possible by the transformation of our democratic practices, our modes of production and consumption, our ways of living together, and our representations (narratives). The success of the transition will depend on its ability to establish social relationships that promote social justice and inclusion (Guay-Boulet, Martin-Déry, & Huot, 2022, p. 24).

The SET will require Quebecers to adopt new ways and means of getting around, housing themselves, feeding themselves, and producing and consuming goods—in short, they will need to change their ways of living (Waridel, 2019). At a time when RDPs are attempting to adjust to the new realities brought about by the climate crisis and to meet the challenges associated with the socioecological transition, there is a great and pressing need for stakeholders to adopt updated and more sustainable approaches.

Denis Bourque, a professor at the Université du Québec en Outaouais, and Sonia Racine, a mobilization advisor at Communagir, are jointly leading a partnership research team whose members have been largely drawn from the schools of social work at four universities: the Université du Québec en Outaouais, the Université de Montréal, the Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue, and the University of Ottawa. Six additional members have been drawn from the Collectif des partenaires en développement des communautés. The project is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Partnership Development Grant # 890-2019-0058). The research team has set out to understand how RDPs, especially those focused on social development, contribute to collective efforts for implementing the SET and fighting the climate crisis. The project aims to shed light on how stakeholders define problems and solutions, and to identify the obstacles and opportunities affecting the ability of RDPs to move the SET forward. It also involves analyzing the role of community workers within RDPs, with a view to understanding their capacity for supporting and integrated approach to development (Lachapelle & Bourque, 2020; Mercier & Bourque, 2021).

Case, Methods, and Original Research Data

In terms of qualitative research, the team has carried out a multiple case study analysis (Stake, 2006) of eight RDPs focused on social development: two local initiatives in Montreal (Solidarité Ahuntsic and Vivre Saint-Michel en santé), two local initiatives in Quebec City (L’Engrenage Saint-Roch and La Ruche Vanier), two initiatives undertaken at the level of regional county municipalities (Tous complices pour notre communauté and Table de développement social Pierre-De Saurel), and two initiatives covering a larger administrative region (Réseau de développement social Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine / Collectif Nourrir notre monde and the Politique régionale de développement social de Laval). The project’s theoretical framework draws on actor-network theory (Akrich, Callon & Latour, 2006) to explain how specific relationships involving human and non-human entities can support the emergence and consolidation of the SET through RDPs. Associated research activities have involved three main data collection methods. To begin with, documentation produced by each of the RDPs concerned (minutes, action plans, annual reports, profiles, etc.) was analyzed with a view to mapping out the trajectories followed by the different initiatives. Next, more than 120 individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with stakeholders (staff members, partners, residents, etc.) to gain a deeper understanding of these initiatives in terms of composition, governance, activities, power relationships, etc. Between 12 and 20 people from each RDP were interviewed. The interviews were transcribed verbatim and the resulting data were processed using category-based and cross-sectional content analysis (Bardin, 2013). Finally, while the interviews were underway, research team members engaged in participant observation at 40 meetings or activities organized by the eight RDPs covered by the study.

Results

In terms of preliminary results, the research team has found that all eight initiatives have led to actions that support the SET (nutrition, transportation, greening, resource sharing, etc.). However, this was not necessarily their stated intention, at least not initially. The RDPs under study were primarily designed to address social needs, although an ecological dimension was added over time. Here are four findings that highlight the progress achieved and obstacles encountered by RDPs seeking to support the SET.

1. The ways in which different initiatives have supported the SET vary depending on whether they operate in an urban, peri-urban, or rural context. The research team identified six areas where the RDPs concerned have made contributions:

A. Nutrition: community gardens operated on the principles of solidarity and cooperation, food-growing communities, greenhouse production, etc.

B. Greening and demineralization: planting (of trees, shrubs, plants, etc.) in available public and private spaces, creation of new green spaces through the removal of concrete and asphalt (expanding the tree canopy), etc.

C. Resource sharing: thrift shops, recycling centres, materials exchange, knowledge sharing, etc.

D. Cleaning: garbage collection, etc.

E. Mobility: complete street design (accessibility for cars, buses, cyclists, pedestrians), green neighbourhood development with a focus on public transit and reduced parking, etc.

F. Housing: community redevelopment of disused sites to meet the need for more social and affordable housing, carbon-neutral buildings, energy-efficient heating systems, etc..

Contributions in certain areas, such as greening and demineralization, were more likely to be associated with RDPs based in urban settings. Contributions in other areas, such as food security and autonomy, were just as likely to be associated with urban initiatives as rural ones (Réseau de développement social Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine, Tous complices pour notre communauté, Table de développement social Pierre-De Saurel).

2. The RDPs under study have traditionally operated based on a hierarchy of needs, prioritizing socio-economic concerns, especially the needs of highly vulnerable individuals, over environmental ones. However, since the start of the study, the research team has observed growing interest in ecologicak matters among the initiatives concerned. The various RDPs have also become much more likely to consider climate and ecological vulnerabilities when assessing regional needs, a trend that has led them to adopt a broader vision of development. For example, in an urban neighbourhood where multiple locations had been identified as heat islands, one group set about lobbying municipal authorities to create more green spaces. But the group in question went even further by encouraging homeowners to plant trees and shrubs on their properties. These actions have not only contributed to the well-being of residents by increasing tree canopy density, but they have also raised public awareness of the importance of natural spaces. In turn, this awareness has led people to take action themselves, whether individually or collectively, and to develop a stronger sense of solidarity. From major projects to small-scale efforts, there are countless opportunities to take action in support of the SET while helping mobilize the widest possible range of local community stakeholders.

The photo on the left shows a parking lot belonging to a company. The photo on the right shows the same location after it was acquired by municipal authorities in Quebec City and transformed into a food park by local residents and members of Engrenage Saint-Roch.

Credits: Engrenage Saint-Roch, 2021

3. Those who speak publicly on ecological issues tend to be ordinary citizens (especially young people), members of environmental groups, and employees of the RDPs like the ones under study who have a background in environmental studies. Those who speak publicly on issues of poverty tend to be members of community associations, the public health community, or the general public. It would therefore appear that grassroots engagement within a given region is often channelled into one of two streams: environmental protection or the fight against poverty. Could community workers draw on their expertise in outreach and relationship building to facilitate communication and interaction between these two streams? Both would draw strength from a closer relationship.

4. It can be difficult to transform even strongly held ideas into action. Most research participants interpreted the SET through a sociocentric lens and therefore shared a belief that “reconfiguring social ties at the local level will produce the innovations needed to drive the transition and make communities more resilient” (Audet, 2017, p. 35). But what stood in the way of action is not just a lack of agreement on how to define the SET, but also a feeling of incompetence or powerlessness. These findings align with the results of a Quebec-wide consultation conducted as part of the États généraux en développement des communautés. It revealed that many people involved in community development initiatives are at a loss when it comes to addressing the SET in that context. At the same time, people involved in grassroots environmental activism find it difficult to connect and collaborate with partners active in social development (Opération veille et soutien stratégique & Collectif des partenaires en développement des communautés, 2022). Another factor that may explain inaction on the part of certain stakeholders is their tendency to view basic needs and acute social issues as immediate concerns. By contrast, the SET tends to be understood from a systemic perspective. As a result, it is associated with medium- or long-term and often larger-scale projects. More than ever, we believe that intersectoral and multi-network cooperation is fundamental to meeting these shared and complex challenges.

Conclusion

The SET will require changes at all levels of society (macro, meso, and micro). At the local or regional level, community development can drive mobilization and thereby serve as a vector for achieving the systemic changes needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and preserve biodiversity. In response to the climate and ecological crisis, the Quebec government has launched a technology-oriented transition, based on the 2030 Plan for a Green Economy. However, this transition carries a high risk of exclusion given its focus on adapting to climate change through individual actions. By contrast, an emphasis on reorganizing society in line with the planet’s finite ecological and energy resources would produce a fairer and more inclusive transition (Audet, 2019). Social inequalities and ecological inequalities affect the same groups, including children, women, seniors, low-income individuals, people with chronic illnesses, Indigenous peoples, and certain categories of workers (Senay and al., 2023). And even if RDPs primarily address social issues, their activities contribute to a broader effort to tackle the climate and environmental crisis. Meanwhile, community workers can support RDPs in aligning their modes of operation and action with those of other community stakeholders, with a view to facilitating collaboration and synergy.

To cite this article

Morin, L., Racine, S., Bourque, D., Parent, A-A., Lachapelle, R., Jetté, C., Grenier, S., Foisy, D., Savard, S., Touba Mbacké Gueye, S., Le Dorze-Cloutier, G., Hamel, A. et Goglio, C. (2024). Community development in the context of the social and environmental transition: Eight Local development processes in Quebec. In Cities, Climate and Inequalities Collection. VRM – Villes Régions Monde. https://www.vrm.ca/developpement-des-communautes-et-transition-socioecologique-etude-de-huit-demarches-de-developpement-territorial-au-quebec-2

Reference Text

Morin, L., Racine, S., Bourque, D., Parent, A.-A., Lachapelle, R., Jetté, C., Grenier, S., Foisy, D., Savard, S. et Mbacké Gueye, S. T. (2023). « Développement des communautés et transition socioécologique : étude de huit (8) démarches de développement territorial au Québec ». Le Cahier du RQIIAC, 5(Printemps), 7‑10.

References

Akrich, M., Callon, M. et Latour, B. (2006). Sociologie de la traduction : textes fondateurs. Paris : Presses des Mines.

Audet, R. (2019, 16 mai). Allocution d’ouverture, Table ronde sur la transition écologique et démocratisation économique : quelles perspectives collectives. https://www.tiess.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Presentation_Rene_Audet.pdf

Audet, R. (2017). « Le discours et l’action publique en environnement ». Dans A. Chaloux (dir.), L’action environnementale au Québec : entre local et mondial (p.19-36). Montréal : Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

Audet, R., Lefèvre, S. et El-Jed, M. (2015). « La mise en marché alternative de l’alimentation à Montréal et la transition socio-écologique du système agroalimentaire ». (1). Les cahiers de recherche OSE.

Bardin, L. (2013). L’analyse de contenu. Presses Universitaires de France. DOI : https://doi.org/10.3917/puf.bard.2013.01

Bilodeau, A., Clavier, C., Galarneau, M., Fortier, M.-M. et Deshaies, S. (2014). Analyse des réseaux d’action locale pour le développement social dans neuf territoires montréalais. Montréal : Léo-Roback, centre de recherche sur les inégalités sociales de santé de Montréal. https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/2435910

Comeau, Y. (2010). L’intervention collective en environnement. Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Courtemanche, A., Bourque, D., Racine, S., Parent, A.-A. et Morin, L. (2022). « Développement des communautés et transition socioécologique au Québec ». 31(2), Organisations et Territoires : 73-84. DOI : https://doi.org/10.1522/revueot.v31n2.1481

Guay-Boulet, C., Martin-Déry, S. et Huot, G. (2022). Économie sociale et transition socioécologique – Quel cadre commun ? Territoires innovants en économie sociale et solidaire. En ligne : https://tiess.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Transition_Synthese.pdf

Huq, S. (2022). Vivre avec 1,1 °C de plus. Dans G. Thunberg (dir.), Le grand livre du climat (p. 158-161). Kero.

Lachapelle, R. et Bourque, D. (2020). Intervenir en développement des territoires. Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Mbacké Gueye, S. T., Morin, L., Bourque, D., Parent, A.-A., Lachapelle, R., Racine, S., Grenier, S., Foisy, D., Jetté, C. et Savard, S. (2023). « Philanthropie de changement social et démarches de développement territorial au Québec : quels types de proximité caractérisent leurs rapports ? » Écrire le social, 1(5), 29‑44. https://doi.org/10.3917/esra.005.0029

Mercier, C. et Bourque, D. (2021). Intervention collective et développement des communautés: éthique et pratiques d’accompagnement en action collective. Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Morin, L., Racine, S., Bourque, D., Parent, A.-A., Lachapelle, R., Jetté, C., Grenier, S., Foisy, D., Savard, S. et Mbacké Gueye, S. T. (2023). « Développement des communautés et transition socioécologique : étude de huit (8) démarches de développement territorial au Québec ». Le Cahier du RQIIAC, 5 (Printemps), 7‑10.

Opération veille et soutien stratégique et Collectif des partenaires en développement des communautés. (2022). Fiches thématiques (11). Opération veille et soutien stratégiques et Collectif des partenaires en développement des communautés.

Organisation mondiale de la Santé (OMS). (2021, 30 octobre). Changement climatique et santé. Centre des médias. Récupéré à : https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health

Parent, A.-A. et Bourque, D. (2016). « La contribution des travailleurs sociaux à la réduction des inégalités sociales de santé ». (143). Intervention. 5-14.

Senay, M.-H., Cunningham, J. et Ouimet, M.-J. (2023). Pour une transition juste : tenir compte des inégalités sociales de santé dans l’action climatique. Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Gouvernement du Québec. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/publications/3342

Stake, R. E. (2006). Multiple case study analysis. Guilford Press.

Waridel, L. (2019). La transition, c’est maintenant : choisir aujourd’hui ce que sera demain. Écosociété.