Emeralde O’Donnell, student researcher, Simon Fraser University and Andréanne Doyon, Assistant Professor and Director of the REM Planning Program, Simon Fraser University, Resource and Environmental Management

Introduction

For decades, scholars have discussed what just, sustainable communities should look like (e.g., Agyeman & Evans, 2003; Schlosberg, 2007; 2013; Hughes & Hoffman, 2020). Still, planning research and practice can use equity and justice terms ambiguously (Winkler, 2018; Pearsall & Pierce, 2010; Finn & McCormick, 2011). Equity relates to fair treatment (e.g., different social groups being able to access the services they need), while justice involves restructuring unfair societal systems (e.g., decolonizing an organization’s practices to increase access to its services). We use these terms together as they are interrelated and often overlap.

How we talk about justice and injustice can impact justice work in planning (Schlosberg, 2007; 2013). This is partly because plans guide how our communities grow and operate, and language shapes the priorities and actions guiding our plans (Barrett et al., 2016). When equity and justice language is vague, it can overlook systemic issues (e.g., unequal power dynamics in decision-making) and hinder action (Winkler, 2018).

With marginalized populations unfairly impacted by climate change (Reckien et al., 2017; Shonkoff et al., 2011) and a history of plans worsening inequity (Schlosberg & Collins, 2014; Adger et al., 2006; Marino & Ribot, 2012; Barnett & O’Neil, 2010; Taylor, 2014), climate and environmental planning cannot leave equity and justice behind. Considering concerns that equity and justice language can impact justice outcomes, our efforts to build a better future should look at both what we want to do and how we talk about it. We explored the link between equity and justice language and justice outcomes within the city of Vancouver, British Columbia, by analyzing content in four recent environmental plans.

State of the scientific literature on the action modality studied

Defining justice

Within environmental justice and planning, scholars most often use a three-pronged framework for justice: distributive, procedural and recognition. This framework is useful for exploring justice work in planning. However, since it has limits in colonial contexts, we argue for a fourth form: epistemic.

Distributive justice focuses on whether the positive and negative impacts of a plan, policy or situation are distributed equitably (Bennett et al., 2019; McCauley & Heffron, 2018; Walker, 2012; Bulkeley et al., 2014). Do low-income individuals disproportionately suffer during heatwaves, while wealthy individuals benefit from the cooling effects of street trees?

Procedural justice considers who is (and is not) included in decision-making, how they are included, what power they have, and what prevents them from participating (Walker, 2012; Bulkeley et al., 2014). Does a wealthy business owner have more influence in decisions, while a working, single parent struggles to find the time and means to attend engagement sessions?

Recognition justice involves several ideas related to acknowledging systemic and historical injustice (Hughes & Hoffmann, 2020) (e.g., historical and ongoing impacts of racist policies) as well as acknowledging and respecting diverse groups with “distinct rights, worldviews, knowledge, needs, livelihoods, histories, and cultures” (Schlosberg, 2007; Walker, 2012; Bennett et al., 2019: 4). Have zoning decisions left racialized and low-income communities disproportionately exposed to landfills? Does a city acknowledge and protect places that are significant to different communities, such as Chinatowns?

Epistemic justice creates space to incorporate diverse perspectives by acknowledging different ways of “doing, being and knowing” as well as acknowledging how unjust systems marginalize non-dominant knowledge (e.g., valuing scientific data over oral histories) (Rodriguez, 2017; Temper, 2019). Do plans honour and incorporate Indigenous or local knowledge? Epistemic justice is particularly relevant in colonial contexts for two reasons: the three-pronged framework does not adequately capture Indigenous values (Hernandez, 2019), and the dominance of Western knowledge contributes to ongoing oppression of Indigenous Peoples (Temper, 2019).

Equity and justice in our cities

Historically, plans have created injustice through a lack of meaningful involvement with residents and by perpetuating distributive and historical injustices (e.g., through discriminatory land use policies) (Schlosberg & Collins, 2014; Adger et al., 2006; Marino & Ribot, 2012; Barnett & O’Neil, 2010; Taylor, 2014).

Research on a variety of early municipal and local government plans (1989‒2012) across the United States, such as plans addressing climate and sustainability issues like transit and street trees, has found that few plans incorporated equity or justice (Warner, 2002; Jabareen, 2014; Bulkeley et al., 2013; Schrock et al., 2015; Portney et al., 2013). For plans that did, actions to address equity or justice issues were vague or non-existent (Warner, 2002; Finn & McCormick, 2011; Jabareen, 2014; Bulkeley et al., 2013; Portney et al., 2013; Pearsall & Pierce, 2010). Research on Canadian plans (2008‒2012) is limited but suggests similar patterns: plans did not explicitly integrate equity and proposed actions were vague and limited (Tozer, 2018).

More recent plans in the United States are focusing on equity and justice, and there are more individual examples of plans that meaningfully address these topics (Schrock et al., 2015; Hess & McKane, 2021). For example, in California, Oakland’s 2030 Equitable Climate Action Plan included a comprehensive “Racial Equity Impact Assessment and Implementation Guide” to support plan actions (Hess & McKane, 2021). However, studies on newer plans in the United States (~2010‒2020) continue to find weak engagement with procedural and recognition justice (Hess & McKane, 2021; Meerow et al., 2019) and a need to better address equity as it relates to marginalized communities (Hess & McKane, 2021).

Much of this research focuses on how much plans engage with justice (e.g., Warner, 2002; Pearsall & Pierce, 2010; Schrock et al., 2015) or which justice issues plans focus on (e.g., Hess & McKane, 2021; Bulkeley et al., 2013). Few studies explore how plans discuss justice, one exception being Meerow et al. (2019), which explores how equity and resilience are framed in resilience plans in the United States.

Original research case, method and data

We analyzed equity and justice language and content in the four most recent environmental plans within the City of Vancouver (as of June 2021). This included language used to define and discuss equity and justice, as well as content that directly or indirectly related to equity and justice.

While each plan has different goals, authors and development processes, all seek to guide work on one or more environmental concerns related to climate change, biodiversity and conservation, or sustainability:

- the Climate Emergency Action Plan (2020) (CEAP) focuses on reducing Vancouver’s emissions;

- the Rain City Strategy (2019) (RCS) focuses on managing rainwater through green infrastructure;

- the Resilient Vancouver Strategy (2019) (RVS) focuses on preparing Vancouver to manage and recover from shocks and stressors (e.g., sea level rise and economic inequity); and

- VanPlay (2018, 2019) (VP) is designed to guide and improve Vancouver’s parks and recreation work.

CEAP, RCS and RVS were authored by the City of Vancouver, while VP was authored by the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation, an independent body that runs the city’s parks and recreation system.

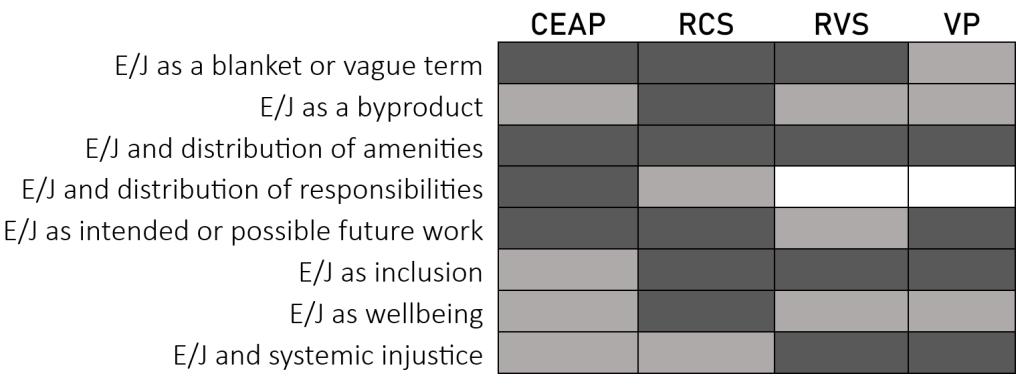

We categorized language and content under two frameworks focusing on (1) how equity and justice is framed and (2) how plans engage with the forms of justice. We identified nine dominant framings related to how plans define and discuss equity and justice. These framings are shown in Figure 1 as being present (framings that occur in a plan at least once) or prominent (framings that occur most often in a plan).

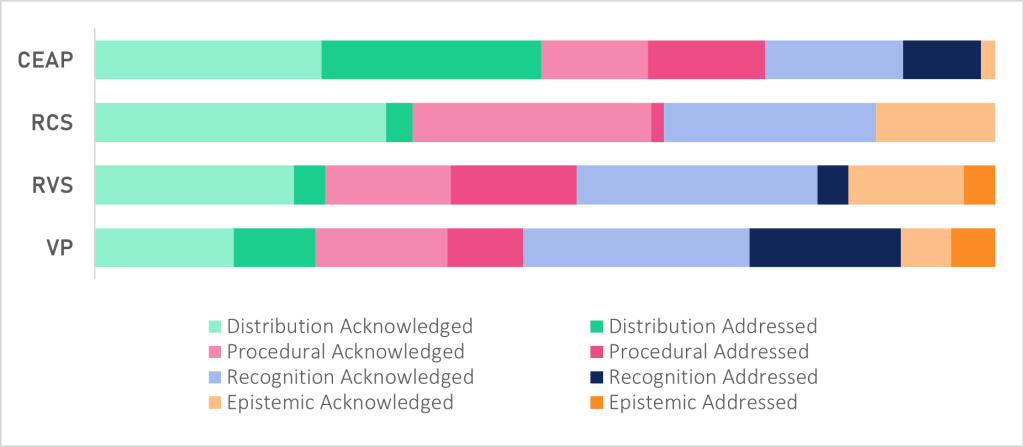

We assessed how plans engage with justice by categorizing content that either (1) acknowledged injustice or the importance of a justice issue or (2) addressed a justice issue either by incorporating it into the plan or proposing actions that related to it. This can be seen in Figure 2, where the proportion of content acknowledging each form of justice is in light shading and the proportion addressing each form of justice is in dark shading.

Results

Distributive-, recognition- and epistemic-acknowledged indicates content where notions of these forms of justice was identified or emphasized as important; procedural-acknowledged refers to instances where public engagement was conducted, public engagement or engagement with marginalized groups was identified as important, or procedural injustice was acknowledged; distributive-, recognition- and epistemic-addressed refers to actions that address injustices related to these forms or explicit plans for action that would address these injustices when implemented; and, because public engagement is now standard practice, procedural-addressed only refers to instances where efforts were made to specifically engage marginalized groups or where feedback from engagement was implemented.

Source: Emeralde O’Donnell & Andréanne Doyon, 2023

Analyzing the plans

When discussing equity and justice, plans primarily use “equity” terminology. Our analyses reflect this. Overall, plans with clearer, more nuanced framings of equity and justice had more diverse and tangible approaches. As seen in Figure 2, CEAP and RCS focus on distributive and procedural justice. In CEAP, equity is largely undefined but focuses on distribution of amenities (benefits), disamenities (negative impacts) and responsibilities (who is required to take actions). Proposed actions focus on distribution, sometimes ignoring other possible issues. For example, CEAP aims to make transit accessible to all and acknowledges safety concerns with transit, yet only proposes to improve affordability and access, equating more routes and more frequent buses with safety. CEAP does not seem to consider other reasons why riders may feel unsafe, such as systemic injustices like racism or sexual violence.

RCS includes definitions of equity and justice concepts in a glossary. However, the plan itself primarily discusses equity in blanket terms, focuses on distributing amenities and frames equity as an automatic byproduct. Rather than exploring how to implement the plan in equitable ways, RCS frames its work as an “essential tool” for achieving vague equity outcomes. Proposed actions often focus on improving general wellbeing rather than equity (e.g., general training programs versus training programs for marginalized groups).

CEAP and RCS only briefly acknowledge systemic injustice. CEAP acknowledges historically discriminatory policies and identifies disproportionate impacts to racialized and low-income communities, while RCS identifies systemic inequalities related to intersecting identities (e.g., gender, race, ability).

RVS shows stronger understandings of systemic injustice but focuses on procedural justice, framing equity as a guaranteed result of participation. The plan focuses on improving equity by involving people who have been excluded rather than proposing actions that address injustices or inequities. RVS acknowledges systems of oppression, such as racism, and proposes actions for specific equity groups (e.g., creating leadership opportunities for people new to the country). However, it rarely identifies barriers that prevent marginalized groups from participating.

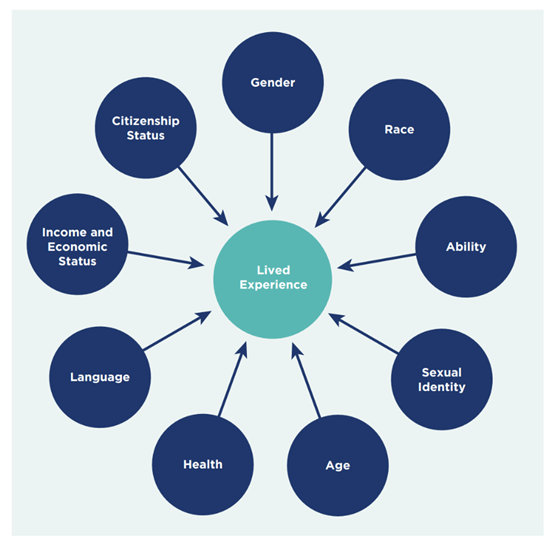

For example, a disabled, straight cisgender woman will have different lived experience than an able-bodied, queer, non-binary person. In acknowledging this diversity of experience, plans might better identify how distributive inequities and systemic injustices impact different people as well as create space for diverse experiences to inform planning work.

Source: City of Vancouver, 2019

Of the four plans, VP has the strongest engagement with epistemic and recognition justice. Equity is defined in its own section based on ideas of power, privilege, oppression and intersectionality. Similar to RVS, VP focuses on “co-creating” systems that serve and empower those excluded. VP proposes clear equity-oriented actions to improve access to recreational services (e.g., creating safe spaces for LGBTQ2S+ visitors). VP does not clearly identify barriers to participation or engage deeply with systemic injustice, and it relies on a distributive tool to improve equity. However, VP is the only plan to regularly acknowledge these limitations in concrete ways, such as by committing to make improvements (e.g., efforts to decolonize the department).

For example, it acknowledges that the system of racism oppresses Indigenous people and people of colour while privileging white people.

Source: Vancouver Board of Parks & Recreation, 2019a

All plans acknowledge Indigenous and local knowledge but rarely incorporate it. Most often, this knowledge is discussed in terms of how the plan can bring benefit or the plan’s authors having more to learn. VP addresses epistemic justice the most, including plans to make space for Indigenous voices and for “equity-seeking groups” to be involved in interpreting data. However, it does not incorporate diverse ways of knowing aside from a brief discussion on Indigenous concepts of wellness.

These focuses on procedural and distributive justice and the limits to recognition justice echo findings from other research (e.g., Pearsall & Pierce, 2010; Bulkeley et al., 2013; Meerow, Pajouhesh & Miller, 2019). In reflecting on these results, we identified possible context-based limitations to the plans’ equity and justice work.

Considering the big picture and the importance of context

With different goals, each plan has to address equity and justice in different ways. For example, CEAP focuses on emissions reduction, and so requires greater focus on distribution of responsibility than VP, which focuses on service delivery. While CEAP has the least balanced approach to justice, it has a higher addressed-versus-acknowledged ratio.

The four plans were also developed differently. RCS builds on a previous plan, which may have made it harder to incorporate new equity and justice work; CEAP was developed within one year, which may have prevented authors from laying solid equity and justice groundwork. The plans with the most holistic engagement with justice, RVS and VP, are both stand-alone plans that had longer development times. VP was also informed by pre-existing equity and justice work, a foundation the other plans did not have. But even VP has disconnects between how equity is framed and which equity and justice issues are addressed. This speaks to greater limitations (e.g., social context, limited knowledge, Vancouver’s city goals).

Scholars have expressed concerns that emphasis on distribution limits justice work by ignoring systemic issues (Hughes & Hoffmann, 2020; Bulkeley et al., 2013; Schrock et al., 2015; Meerow et al., 2019; Hess & McKane, 2021). We have found similar weaknesses and advocate for plans to meaningfully engage with every form of justice. However, it is hard to determine how limited a plan is, and why, without considering the unique factors influencing it. Winkler (2018, p. 82) argues we must consider what a planning decision means in a particular context before deciding what is “good.” For example, different planning goals might naturally emphasize different forms of justice.

Current research has focused not only on which justice issues plans engage with, and to what extent, but has also examined trends across several plans over large geographic areas (e.g., Fitzgibbons & Mitchell, 2019; Olazabal & Ruiz De Gopegui, 2021; Hess & McKane, 2021; Schrock et al., 2015; Bulkeley et al., 2013; Pearsall & Pierce, 2010). While much research compares plans with similar purposes, each planning problem in every city will have different justice needs.

Schrock et al. (2015) demonstrate the value of a narrower scope through case studies. By examining plans more closely, the authors identified key contextual factors limiting equity and justice work. If we do this in a single city, we can better unpack what influences and limits a plan within that city.

Including epistemic justice within research could be one way to consider context more closely. Engaging with epistemic justice requires you to understand the specific needs, values and worldviews of a plan’s people and places. This can add more nuance by creating space to analyze justice through the lens of the community versus under a general framework of what justice should look like.

Conclusion

Broad studies have highlighted weaknesses in how plans have incorporated equity and justice. Now that plans are making more tangible efforts towards these goals, we argue that more research should have narrower scopes. By exploring how specific plans engage with equity and justice issues within particular contexts, such as through analyzing language, we can ask questions about what unique factors might limit the plans.

The ways we talk about justice inform how we use, understand and “demand [justice] in practice” (Schlosberg, 2013). While equity and justice framings alone are unlikely to determine the justice outcomes of the studied plans, these framings likely reflect how equity and justice were discussed and understood during each plan’s development.

Of the plans analyzed, the ones most engaged with justice included specific and thoughtful understandings of equity and justice concepts, and these understandings appeared to inform the plans early in development. For planners, this highlights a need to intentionally embed nuanced equity and justice ideas early on in planning work.

While our work did not explore citizen engagement, it highlights the value of carefully considering how we, as citizens, talk about and understand the unique equity and justice issues within our cities. As citizens, we might reflect on the ways we advocate for equity and justice: being precise and intentional in our calls for change could foster meaningful priority-setting towards cities that are both sustainable and just.

To cite this article

O’Donnell, E., and Doyon, A. (2024). Exploring equity and justice content in Vancouver’s environmental plans. In Cities, Climate and Inequalities Collection. VRM – Villes Régions Monde. https://www.vrm.ca/examen-des-considerations-en-matiere-dequite-et-de-justice-dans-les-plans-environnementaux-de-vancouver-2

Reference text

O’Donnell E and Doyon A (2023) Language, context, and action: exploring equity and justice content in Vancouver environmental plans. Local Environment. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2023.2238734

References

Agyeman J et Evans T (2003) Toward Just Sustainability in Urban Communities: Building Equity Rights with Sustainable Solutions. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 590(1): 35–53. doi:10.1177/0002716203256565.

Barnett J et O’Neill S (2010). Maladaptation. Global Environnemental Change 20(2): 211–213. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.11.004.

Barrett BFD, Horne R et Fien J (2016) The Ethical City: A Rationale for an Urgent New Urban Agenda. Sustainability 8(11): 1197. doi:10.3390/su8111197.

Bennett NJ, Blythe J, Cisneros-Montemayor AM, Singh GG et Sumaila UR (2019) Just Transformations to Sustainability. Sustainability 11(14): 3881.

Bulkeley H, Carmin J, Castán Broto V, Edwards GAS et Fuller S (2013) Climate Justice and Global Cities: Mapping the Emerging Discourses. Global Environmental Change 23(5): 914–925. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.05.010.

Bulkeley H, Edwards GAS et Fuller S (2014) Contesting Climate Justice in the City: Examining Politics and Practice in Urban Climate Change Experiments. Global Environmental Change 25(1): 31–40. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.01.009

CEAP: City of Vancouver (2020) Climate Emergency Action Plan.

Finn D and McCormick L (2011) Urban Climate Change Plans: How Holistic?. Local Environment 16(4): 397–416. doi:10.1080/13549839.2011.579091.

Fitzgibbons J et Mitchell CL (2019) Just Urban Futures? Exploring Equity in ‘100 Resilient Cities.’ World Development 122: 648–659. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.06.021.

Granberg M et Glover L (2021) The Climate Just City. Sustainability 13(3): 1201. doi:10.3390/su13031201.

Hernandez J (2019) Indigenizing Environmental Justice: Case Studies from the Pacific Northwest Environmental Justice 12(4): 175–181. doi:10.1089/env.2019.0005.

Hess DJ et McKane RG (2021) Making Sustainability Plans More Equitable: An Analysis of 50 U.S. Cities. Local Environment 26(4): 461–476. doi:10.1080/13549839.2021.1892047.

Hughes S (2013) Justice in Urban Climate Change Adaptation: Criteria and Application to Delhi. Ecology and Society 18(4). doi:10.5751/ES-05929-180448.

Hughes S et Hoffmann M (2020) Just Urban Transitions: Toward a Research Agenda. WIREs Climate Change 11(3). doi:10.1002/wcc.640.

Jabareen Y (2014) An Assessment Framework for Cities Coping with Climate Change: The Case of New York City and Its PlaNYC 2030. Sustainability 6(9): 5898–5919. doi:10.3390/su6095898.

Marino E et Ribot J (2012) Special Issue Introduction: Adding Insult to Injury: Climate Change and the Inequities of Climate Intervention. Global Environmental Change, Adding Insult to Injury: Climate Change, Social Stratification, and the Inequities of Intervention 22(2): 323–328. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.03.001.

McCauley D et Heffron R (2018) Just Transition: Integrating Climate, Energy and Environmental Justice. Energy Policy 119: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.014.

Meerow S, Pajouhesh P et Miller TR (2019) Social Equity in Urban Resilience Planning. Local Environment 24 (9): 793–808. doi:10.1080/13549839.2019.1645103.

Olazabal M et Ruiz De Gopegui M (2021) Adaptation Planning in Large Cities Is Unlikely to Be Effective. Landscape and Urban Planning 206:103974. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103974.

Pearsall H et Pierce J (2010) Urban Sustainability and Environmental Justice: Evaluating the Linkages in Public Planning/Policy Discourse. Local Environment 15(6): 569–580. doi:10.1080/13549839.2010.487528.

Portney K, Kamieniecki S et Kraft ME (2013) Taking Sustainable Cities Seriously: Economic Development, the Environment, and Quality of Life in American Cities. American and Comparative Environmental Policy. Cambridge: MIT Press. doi:10.7551/mitpress/6617.001.0001.

RCS: Conger T, Couillard A, de Hoog W, Despins C, Douglas T, Gram Y, Javison J, et al. (2019) Rain City Strategy: A Green Rainwater Infrastructure and Rainwater Management Initiative. City of Vancouver.

Reckien D, Creutzig F, Fernandez B, Lwasa S, Tovar-Restrepo M, Mcevoy D et Satterthwaite D (2017) Climate change, equity and the Sustainable Development Goals: an urban perspective. Environment and Urbanization 29(1): 159–182. doi:10.1177/0956247816677778

Rodriguez I (2017) Linking Well-Being with Cultural Revitalization for Greater Cognitive Justice in Conservation: Lessons from Venezuela in Canaima National Park. Ecology and Society 22(4): 24.

RVS: City of Vancouver (2019) Resilient Vancouver Strategy.

Schlosberg D (2007) Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Schlosberg D (2013) Theorising Environmental Justice: The Expanding Sphere of a Discourse. Environmental Politics 22(1): 37–55.

Schlosberg D et Collins LB (2014) From Environmental to Climate Justice: Climate Change and the Discourse of Environmental Justice. WIRES Climate Change 5(3): 359–374. doi:10.1002/wcc.275.

Schrock G, Bassett EM, and Green J (2015) Pursuing Equity and Justice in a Changing Climate: Assessing Equity in Local Climate and Sustainability Plans in U.S. Cities. Journal of Planning Education and Research 35(3): 282–295. doi:10.1177/0739456X15580022.

Shonkoff SB, Morello-Frosch R, Pastor M et Sadd J (2011) The climate gap: environmental health and equity implications of climate change and mitigation policies in California—a review of the literature. Climatic Change 109: 485–503. doi:10.1007/s10584-011-0310-7

Taylor DE (2014) Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility. New York: New York University Press.

Temper L (2019) Blocking Pipelines, Unsettling Environmental Justice: From Rights of Nature to Responsibility to Territory. Local Environment 24(2): 94–112.

Tozer L (2018) Urban Climate Change and Sustainability Planning: An Analysis of Sustainability and Climate Change Discourses in Local Government Plans in Canada. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 61(1): 176–194. doi:10.1080/09640568.2017.1297699.

VP: Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation (2018a) VanPlay Report 1: Inventory and Analysis.

VP: Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation (2018b) VanPlay Report 2: 10 Goals to Shape the Next 25 Years.

VP: Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation (2019a) VanPlay Report 3: Strategic Bold Moves.

VP: Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation (2019b) VanPlay Report 4: The Playbook: Implementation Plan.

VP: Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation (2020) VanPlay: Vancouver Parks and Recreation Framework.

Walker G (2012) Environmental Justice: Concepts, Evidence and Politics. London: Routledge.

Warner K (2002) Linking Local Sustainability Initiatives with Environmental Justice. Local Environment 7(1): 35–47. doi:10.1080/13549830220115402.

Winkler, T (2018) Rethinking Scholarship on Planning Ethic. Dans: Gunder M, Madanipour A, and Watson V (eds) The Routledge Handbook of Planning Theory. New York: Routledge, pp.81–92. doi:10.4324/9781315696072-7.