Geneviève Vachon, professor (École d’Architecture de l’Université Laval), Florence Gagnon, research professional (École d’Architecture de l’Université Laval), Élisa Gouin, Ph.D in architecture (École d’Architecture de l’Université Laval) et Samuel Boudreault, research professional (École d’Architecture de l’Université Laval)

Introduction

The pressing realities and concerns that face Indigenous communities in search of self-determination are being exacerbated by climate change. Because their cultures and well-being are based on a close relationship with the land and its ecosystems, these communities are disproportionately and, it could easily be argued, unjustly impacted by how the climate crisis is altering their living environments and lifeways (Galway et al., 2022).

The Anishinaabe community of Barriere Lake, located within the boundaries of Quebec’s La Vérendrye wildlife reserve (HLNQ, 2023), provides a case in point. In 2021, community members, a research team from Université Laval, and representatives from the Ministère des Transports et de la Mobilité durable (MTMD, the provincial department responsible for transportation and sustainable mobility) came together in a “partnership space.” Their aim was to reflect on how the Indigenous relationship with the land and Indigenous knowledge could inform efforts to develop the reserve in a sustainable and culturally sensitive manner, given a proposal to build a new service area along Route 117 (Vachon et al., 2023). A detailed community plan emerged from the research-creation project that ran from January to May 2023. And because land-use planning is a form of climate action, the plan focused on fostering resilient adaptation in the community. Along with five researchers (including two master’s students), the project drew on the knowledge and expertise of some ten members of the Barriere Lake community, three MTMD representatives, and five planners working in the fields of urban design, landscape architecture, and land-use planning. Two of the professionals in the latter group were Indigenous.

On a conceptual level, three fundamental components of Indigenous understandings of the land—traditional knowledge, temporality, and relationality—proved key to addressing climate change from an Indigenous perspective. In terms of methodology, the development of a collaborative research framework based on a community partnership helped ensure that local issues would be considered and that Anishinaabe land-use goals would be pursued. Finally, at an operational level, the research-creation process facilitated the development of an urban design scenario for the Barriere Lake community in which the adaptation of living environments could provide a basis for climate change discussions and actions.

State of the Academic Literature

In addition to being exacerbated by the legacy of colonialism (Nursey Bray et al., 2022), the effects of climate change are felt by Indigenous communities on a daily basis. Relevant impacts include the disappearance of cultural practices, food insecurity, resource destruction, and a substandard built environment that is vulnerable to severe weather (Kenney et al., 2023; Willox et al., 2012). Moreover, Indigenous identities and values are generally based on a close relationship with the land, which remains an important focus of cultural practices and expressions. In the context of the climate crisis, three aspects of this relationship are key to understanding how vital it is to Indigenous realities and worldviews.

Indigenous Knowledge

Traditional Indigenous knowledge stems from observation and experience of the land. It perceives the human experience as inextricably tied to the natural world (Kimmerer, 2013). Far from static, such knowledge is in constant development as it is transferred from generation to generation, adapting to changing conditions on the land (Nursey Bray et al., 2022). As a result, insofar as climate change is impacting the relationship between Indigenous people and the land, the loss of knowledge threatens not only cultural survival but also the continuity of subsistence activities critical to food security (Galway et al., 2022).

That said, Indigenous people refuse to be passive victims of climate change (Nursey Bray et al., 2022). Having long ago sounded the alarm about a pattern of wrongful dispossession and unfair decline, many have set about gathering knowledge, experience, and skills relevant to climate action and adaptation. Although the discourse remains dominated by a Western scientific establishment that has long denied the value and legitimacy of Indigenous knowledge systems, the latter are being increasingly recognized for their ability to support efforts for mitigating climate change and promoting sustainability (Kenney et al., 2023; McGegor et al., 2023). In Canada, at the local level, cultural practices and knowledge are rooted in meaningful places that communities find threatened by climate disaster. Examples of these threats include the devastation of First Nations lands by forest fires and the loss of sea ice and permafrost in Inuit territories. Such impacts lead to food insecurity by limiting access to subsistence resources, especially animals and plants (Koperqualuk, 2023; Willox, 2012).

Temporality

Because it is a construct, time is perceived differently by Indigenous communities that understand and experience their relationship with the land in terms of seasonal rhythms and cycles (Gentelet, 2009). Such communities are conscious of how the future is being shaped by the environmental impact of human actions taken today and in the past (Gabriel, 2023). This relationship with time and the seasons, grounded in the close observation of ecosystems, forms part of an evolving system of traditional knowledge. It also shapes subsistence and knowledge transmission practices (Hatfield et al., 2018; Kassam, 2021). In recent times, the sedentary lifestyle imposed on semi-nomadic Indigenous peoples has altered their movements and their relationship with the seasons. But despite everything, including the fact that present-day routines relate to time in different and sometimes hard-to-reconcile ways, the connection with the land persists in everyday life as well as in the collective imagination (André-Lescop, 2019). At the same time, climate change continues to disrupt Indigenous temporalities in ways that seem increasingly difficult for communities to overcome (Koperqualuk, 2023; Turner & Clifton, 2009).

Relationality

Clearly, climate change is damaging the Indigenous relationship with nature. In this context, the concept of relationality (Wilson, 2008) refers to how Indigenous peoples understand their interactions with the environment and the land in terms of a reciprocal relationship. In turn, this reciprocity is based on the notion of caretaking. Geographic proximity between home and the land only serves to strengthen this relationship: “By reducing the space between things, we are strengthening the relationship that they share” (Wilson, 2008, p. 87). Climate risks and their impact on the land alter this reciprocity and the ability to envision appropriate adaptation measures. From a holistic perspective, the land plays a central role in planning decisions made at the community level (Matunga, 2013). So how can land-use planning help minimize the negative impacts of climate change on the relationship between Indigenous people and the land?

In short, the effects of climate change on Indigenous communities are often unfairly amplified because of how they threaten the environmental, spatial, spiritual, and symbolic foundations of Indigenous knowledge and lifeways. This form of environmental injustice is all the more painful and disproportionate for typically small Indigenous communities whose members live in what are often precarious circumstances (Pouliot, 2023). But at the same time, knowledge and teachings rooted in those same communities hold part of the solution to the climate crisis (Gabriel, 2023).

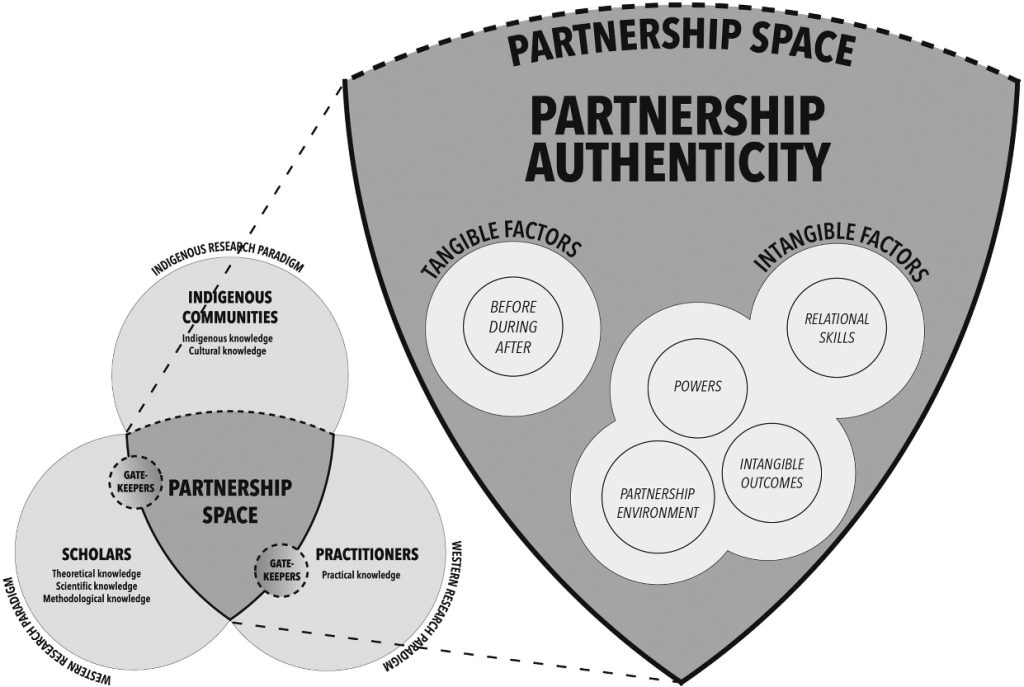

Case, Methods, and Original Research Data

The potential expansion of the woodland community of Barriere Lake provides an interesting illustration of these realities. Related development would include the construction of a new service area along Route 117. To better reflect on the process, the Anishinaabeg, the Living in Northern Quebec team at Université Laval, and the MTMD launched a collaborative research-creation project that took shape within a partnership space where the interests, knowledge, and experience of all stakeholders were considered. Of course, this space was not immune to tensions resulting from the clash of Western and Indigenous perspectives or the kind of assumptions that have contaminated past collaborations. Rather than trying to gloss over such issues, the knowledge co-construction process used the partnership space as a context for relationship building and dialogue between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. These efforts relied on “gatekeepers” capable of travelling between paradigms to help reveal “hyphens” that could serve as the basis for a useful and sustainable collaborative approach (Bussières, 2018; Gentelet, 2009; Jones & Jenkins, 2008). Such a space of mutual trust reflects the type of relationship symbolized by the “Two Row Wampum, a treaty of peaceful coexistence between settlers and First Nations” (Viswanathan, 2019). Ultimately, the success (or lack thereof) of a research partnership depends on a number factors, both tangible and intangible, that determine its level of authenticity (Figure 1).

Reference: Gouin, 2021

In the context of the study undertaken in collaboration with the Anishinaabeg of Barriere Lake, different engagement activities helped operationalize the partnership space while informing the research-creation project known as Let’s have a yarn! These activities included site visits and field interviews; a living environment analysis, which considered concepts such as housing clusters (Corrivault-Gascon, 2023) and mobility (Gagnon, 2023); the analysis of architectural precedents; the elaboration of a timeline identifying milestones in the resurgence of community engagement (HLNQ, 2023); and a preliminary architectural design workshop with community members and MTMD representatives. Engagement efforts provided opportunities to learn about local issues, including those related to climate change, such as reduced access to the land due to the destruction of camps and resources by forest fires.

Let’s have a yarn! was designed to explore the relationship between the Anishinaabeg and the land they call home, with the aim of considering the community’s future expansion in a context of climate change. In addition to community and MTMD representatives, Indigenous and non-Indigenous planners participated in the project. At the turn of the 21st century, these planners had produced an expansion plan, which was never implemented (Eide, n.d.).

Results

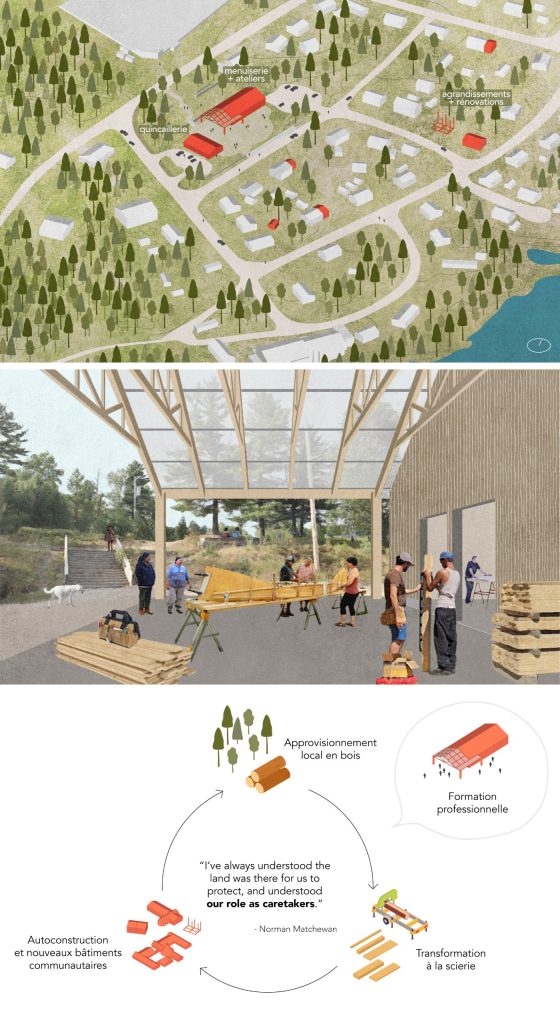

References: Corrivault-Gascon & Gagnon, 2023, as presented in the plan prepared by Atelier Braq

The forest fires that ravaged northwestern Quebec in summer 2023 highlighted the importance of thinking about the impacts of climate change on the relationship between the Barriere Lake community and the land. Indeed, several of the family camps that help define the Anishinaabe cultural landscape were threatened or lost. The community responded by taking concrete measures, including by having more than 40 residents take training offered by the Société de protection des forêts contre le feu (the Quebec agency responsible for forest fire management) and by cutting a fire break near the reserve (according to Facebook posts and on-site partners). During the same period, the Westbank First Nation in British Columbia took similar action through the Ntityix Development Corporation, whose forest fire prevention techniques based on Indigenous knowledge have been proven effective.

According to Barriere Lake community member Norman Matchewan, the Anishinaabe way of life is “inseparable” from the land (Barriere Lake Solidarity, 2011). Many families divide their time between the community and the forest, with the latter serving as a place for hunting, fishing, trapping, gathering, crafting, and practising traditional medicine. Matchewan has also explained how the relationship with the land is fundamental to Anishinaabe identity: “It is our home. I grew up connected to the land. […] And it is how our identity survives, as Mitchikinabikok Inik” (Pasternak, 2017, p. 85).

From a relational perspective, climate change has a direct impact on the relationship that binds a community to the land as a place of subsistence, as well as a place for revitalization and identity affirmation where knowledge takes root. The illustrated narrative published in the context of the Let’s have a yarn! project presents various planning scenarios designed to preserve and enhance the relationship with the forest, which plays the role of protagonist (Figure 2).

The construction of new community infrastructure has been planned in a way that will have minimal impact on the forest environment, and with special attention to preserving the large pine tress that are essential to the spirit of the site. The proposal for expanding the reserve includes no built structures within the community circle. The latter will simply be cleared so it can host various events, including outdoor classes, community celebrations, and knowledge sharing workshops with elders (Figure 3). This example prompts a reassessment of the role played by planners in a woodland context: They can better care for the forest by pursuing reversible forms of development that leave as few traces as possible.

Reference: Autors, 2023

The project also drew inspiration from the Innu notion of E nutshemiu itenitakuet or forest atmosphere (Bellefleur, 2019), which focuses attention on factors that are essential to the preservation of cultural practices. In an Anishinaabe context, the notion can be found reflected in strategies for preserving and enhancing the forest ecosystem: selective or partial cutting, maintaining connections between forest stands, ensuring water quality, and protecting mature trees.

At the same time, the project emphasized the exercise of agency by the Anishinaabeg, especially in terms of managing the forest as a living environment. For instance, it led to a proposal for repurposing the current site of the elementary school as a carpentry centre with workshops (Figure 4). Amid a housing shortage, such facilities can provide support and encouragement to community members interested in embarking on renovations and do-it-yourself projects. They can also be used to train the young construction workers and tradespeople needed to implement future changes to the built environment. The construction of a sawmill like the one in Kitcisakik (Lévesque, 2017) would ensure a local and sustainable supply of construction materials. In fact, trees cut down to make way for new infrastructure could be made into boards or logs to be used in construction. Wood cleared for fire breaks or damaged in forest fires could also be used in this way, and lumber from demolished buildings could be recycled. Ultimately, land-use planning strategies like these are designed to shorten the wood supply chain in a way that helps prevent forest fires and leaves a smaller carbon footprint. Drawing on its experience and knowledge, the community would take responsibility for forest management and logging. The seven generations model would provide a framework for a planning process aligned with Indigenous worldviews: “The knowledge of the past informs the present and, together, it builds a vision towards the future” (Jojola, 2013, p. 457).

Reference: Autors, 2023

Building on the development plan prepared by Atelier Braq (Eide, n.d.), the proposal focuses on the creation of family housing clusters inspired by traditional hunting camps. Building homes in a woodland environment would help maintain close ties with the forest while ensuring the persistence of lifestyles and cultural practices tied to the land, as well as associated knowledge. Indeed, traditional Anishinaabe knowledge flows directly from the experience of living on the land: “This knowledge is the repository of hundreds of generations of Algonquins who have lived on the territory” (Pasternak, 2017, p. 81). Accordingly, the project developed a new land-use plan for the community. Whereas the configuration and density of the existing reserve reflect a break with traditional ways of inhabiting the land, a more “spread out” approach has the potential to strengthen community resilience in the face of potential forest fires. Along with a new community centre, these clusters are therefore intended to restore the forest’s role as a living environment, thereby helping ensure the transmission of cultural practices.

Furthermore, a forest-based lifestyle is directly connected to notions of temporality: animal migrations, plant growth, snowmelt, etc. The repetition—or disruption—of seasonal cycles serves to amplify changes in the land and changing land-use patterns. By seeking to preserve traditional ways of life on the land, the proposal recognizes the role of the Anishinaabeg as caretakers and sentries capable of spotting ecosystem disruptions caused by changing conditions. Meanwhile, the creation of family housing clusters reflects the community’s landholding traditions. As former Chief Jean-Maurice Matchewan has explained, “The territory is divided up among families, each one is responsible for the care of an area” (Pasternak, 2017, p. 2). The proposal therefore seeks to organize land use in the community based on a reciprocal relationship between the Anishinaabeg and the land, with the aim of preserving the land for future generations.

In short, the Let’s have a yarn! project led to a proposal for adapting “urban” design practices to a woodland environment in a way that strengthens a relationship essential for protecting and renewing knowledge that stems from life on the land, all without denying the inherently modern aspects of development. In this way, the study illustrates how architecture and land-use planning can provide ways of adapting living environments to climate change that are aligned with core aspects of Anishinaabe identity.

Conclusion

Rethinking land-use planning in Indigenous communities from a sustainable and culturally sensitive perspective while also addressing the threat of climate change means recognizing the knowledge that stems from these communities’ reciprocal relationship with the land. By taking an authentically collaborative approach, it becomes possible to forge partnerships with First Nations and other stakeholders that allow for drawing on different forms of knowledge and different worldviews. This facilitates efforts to plan living environment adaptations that are both acceptable and feasible. Environmental justice for Indigenous peoples subject to the impacts of climate change can only be achieved through the decolonization of research and planning methods. At the same time, Indigenous peoples in search of self-determination are committed to exercising full control over efforts to protect their lands. That way, they can ensure that all implemented measures fully align with their values, practices, and knowledge (Koperqualuk, 2023).

To cite this article

Vachon, G., Gagnon, F., Gouin, É. et Boudreault, S. (2024). The central importance of relationality for climate action and culturally sensitive land-use planning in Indigenous territories. In Cities, Climate and Inequalities Collection. VRM – Villes Régions Monde. https://www.vrm.ca/la-relationalite-au-coeur-des-enjeux-climatiques-et-damenagement-culturellement-approprie-en-territoires-autochtones-2

Reference Texts

Corrivault-Gascon, A., Gagnon, F. (2023). Let’s have a yarn! An illustrated narrative to reveal and imagine Kitiganik. Projet de fin d’études en design urbain, École d’architecture, Université Laval, Québec. Disponible à : https://aa24f80f-8b99-4378-b0e9-b8399fdb9ea6.filesusr.com/ugd/2475f9_7666a38a4b7d48ff960b7f47711d9e1a.pdf

Vachon, G., Gouin, E., Boudreault, S. (2023). « La réconciliation dans l’action : construire un cadre collaboratif d’aménagement avec une communauté anishinaabe », numéro thématique Adopter une vision renouvelée du territoire, Urbanité, Revue de l’ordre de urbanistes du Québec. Printemps/été 2023 : 26-29.

References

Barriere Lake Solidarity (2011) Algonquins of Barriere Lake vs Section 74 of the Indian Act. Disponible à : https://vimeo.com/23103527 (consulté le 16 mai 2023).

Bellefleur, P (2019) E nutshemiu itenitakuet : un concept clé à l’aménagement intégré des forêts pour le Nitassinan de la communauté innue de Pessamit. Mémoire de maîtrise, Université Laval, Québec.

Corrivault-Gascon, A, Gagnon, F (2023) Let’s have a yarn! An illustrated narrative to reveal and imagine Kitiganik. Projet de fin d’études en design urbain, École d’architecture, Université Laval, Québec. Disponible à : https://aa24f80f-8b99-4378-b0e9-b8399fdb9ea6.filesusr.com/ugd/2475f9_7666a38a4b7d48ff960b7f47711d9e1a.pdf

Corrivault-Gascon, A (2023) Récits visuels de l’appropriation de l’espace résidentiel autochtone : Les cas des Anishinaabeg de Kitiganik. Essai en design urbain, Université Laval, Québec.

Eide, W (s.d.) Learning from Kitiganik. Blogue Bicycle Fixation. Disponible à : https://www.bicyclefixation.com/kiti.htm (consulté le 10 septembre 2023).

Gabriel, KE (2023) Justice et injustice autochtones, européennes et environnementales, dans Kahn, S et Hallmich, C (dir.) La nature de l’injustice : Racisme et inégalités environnementales. Éditions Écosociété.

Gagnon, F (2023) De mobilité à relationalité : Une esquisse de la région de mobilité de la communauté anishinaabe de Barriere Lake. Essai en design urbain, Université Laval, Québec.

Galway, LP, Esquega, E, Jones-Casey, K (2022) ‘Land is everything, land is us’: Exploring the connections between climate, land, and health in Fort Willams First Nation. Social Science and Medicine 294: 11 4700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114700

Gouin, E. (2024). Recherche partenariale en aménagement et en architecture: Conditions d’un partenariat authentique. Thèse de doctorat, Université Laval, Facult. d’aménagement, d’architecture, d’art et de design.

Gouin, E. (2021) Research Partnerships in Planning and Architecture in Indigenous Contexts: Theoretical Premises for a Necessary Evaluation, Journal of Community Practice, 29 (2): 133-152. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2021.1938769.

Habiter le Nord québécois (2023) Habiter ici : Portrait de cinq communautés anishinaabeg du Nitakinan. Sous la direction de G Vachon, S Boudreault, É Gouin, édité par C Baril. École d’architecture de l’Université Laval, Québec.

Hatfield, SC, Marino, E, Whyte, KP, Dello, KD, Mote, PW (2018) Indian time: time, seasonality, and culture in Traditional Ecological Knowledge of climate change. Ecological Processes 7 (25). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-018-0136-6

Jojola, TS (2013) Indigenous Planning : Towards a Seven Generations Model, dans Natcher, DC, Walker, RC, Jojola, TS (dir.) Reclaiming Indigenous planning. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Kassam, K-A (2021) Transdisciplinary research, Indigenous knowledge, and wicked problems. Rangelands 43 (4): 133-141. doi 10.1016/j.rala.2021.04.002

Kenney, C, Phibbs, S, Meo-Sewabu, L, Awatere, S, McCarthy, M, Kaiser, L. Harmsworth, G, Harcourt N, Taylor, L, Douglas, N, Kereopa, L (2023) Indigenous Approaches to Disaster Risk Reduction, Community Sustainability, and Climate Change Resilience (chapitre 2), dans Estamian, S, Estamian F (dir.) Disaster Risk Reduction for Resilience: Climate Change and Disaster Risk Adaptation. NY: Springer.

Kimmerer, RW (2013) Braiding Sweetgrass : Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Milkweed Editions : Minneapolis.

Koperqualuk, L (2023) Réalités Inuit au Nunavik, disparition des terres et incidences sur la subsistance, dans Kahn, S et Hallmich, C (dir.) La nature de l’injustice : Racisme et inégalités environnementales. Éditions Écosociété.

Lévesque, G (2017) Habitations autochtones à Kitcisakik : projet de rénovation, de transfert de connaissances et valorisation des compétences locales, 2008-2020. Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, 47(1) : 173-183. https://doi.org/10.7202/1042909ar

Matunga, H (2013) Theorizing Indigenous planning, dans Natcher, DC, Walker, RC, Jojola, TS (dir.) Reclaiming Indigenous planning. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

McGregor, D, Littlechild, D, Sritharan, M (2023) The role of traditional environmental knowledge in planetary well-being (chapitre 20), dans Ruckstuhl, K, Velasquez Nimatuj, IA, McNeish, J-A, Postero, N (eds) Indigenous futurities: The Routledge Handbook of Indigenous Development. London: Routledge. DOI: 10.4324/9781003153085-24

Nursey-Bray, M, Palmer, R, Chischilly, AM, Rist, P, Yin, L (2022a) Introducing Indigenous Peoples and Climate Change (chapitre 1), dans Old Ways for New Days. Springer Briefs in Climate Studies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97826-6_3

Nursey-Bray, M, Palmer, R, Chischilly, AM, Rist, P, Yin, L (2022b) Indigenous Adaptation – Not Passive Victims (chapitre 3), dans Old Ways for New Days. Springer Briefs in Climate Studies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97826-6_3

Nursey-Bray, M, Palmer, R, Chischilly, AM, Rist, P, Yin, L (2022c) Old ways for new days (chapitre 7), dans Old Ways for New Days. Springer Briefs in Climate Studies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97826-6_3

Pasternak, S (2017) Grounded authority : The Algonquins of Barriere Lake against the state. University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis.

Pouliot, Y (2023) Pollution et santé dans l’Arctique canadien : un survol, dans Kahn, S et Hallmich, C (dir.) La nature de l’injustice : Racisme et inégalités environnementales. Éditions Écosocitété.

Ruckstuhl, K, Velasquez Nimatuj, IA, McNeish, J-A, Postero, N (2022) Rethinking Indigenous development (Introduction), dans Indigenous futurities: The Routledge Handbook of Indigenous Development. London: Routledge.

Turner, NJ, Clifton, H (2009) ‘It’s so different today: Climate change and Indigenous lifeways in British Columbia, Canada. Global Environmental Change 19 (2009): 180-190. DOI:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.01.005

Vachon, G, Gouin, E, Boudreault, S (2023) La réconciliation dans l’action : construire un cadre collaboratif d’aménagement avec une communauté anishinaabe, numéro thématique Adopter une vision renouvelée du territoire, Urbanité, Revue de l’ordre de urbanistes du Québec. Printemps/été 2023 : 26-29.

Viswanathan, L (2019) Planning with empathy. Ballado 360 degree city, 10 juin. Disponible à: https://360degree.city/2019/06/10/planning-with-empathy/

Willox, AC, Harper, SL, Ford, JD, Landman, K, Houle, K, Edge, VL, Rigolet Inuit Community Government (2012) ‘From this place and of this place’: Climate change, sense of place, and health in Nunatsiavut, Canada. Social Science & Medecine 75: 538-547. DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.043

Wilson, S (2008) Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Halifax: Fernwood.